Research highlights

Competition for time:

A novel mechanism of biodiversity maintenance

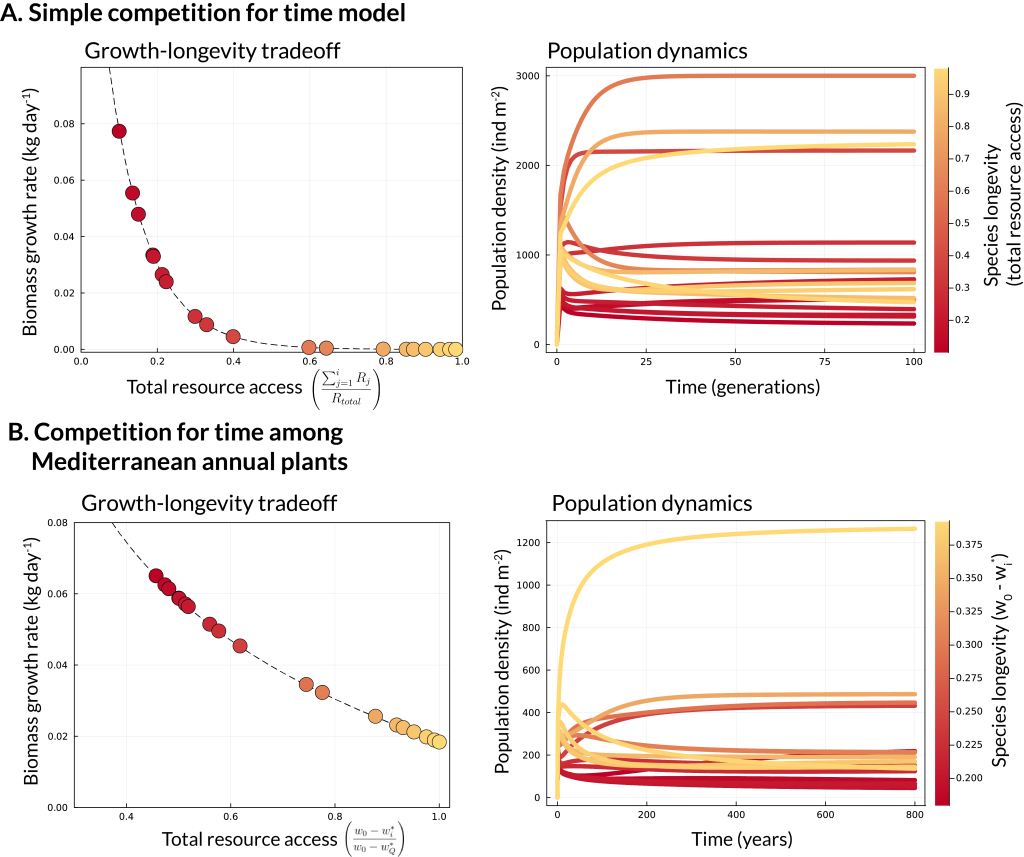

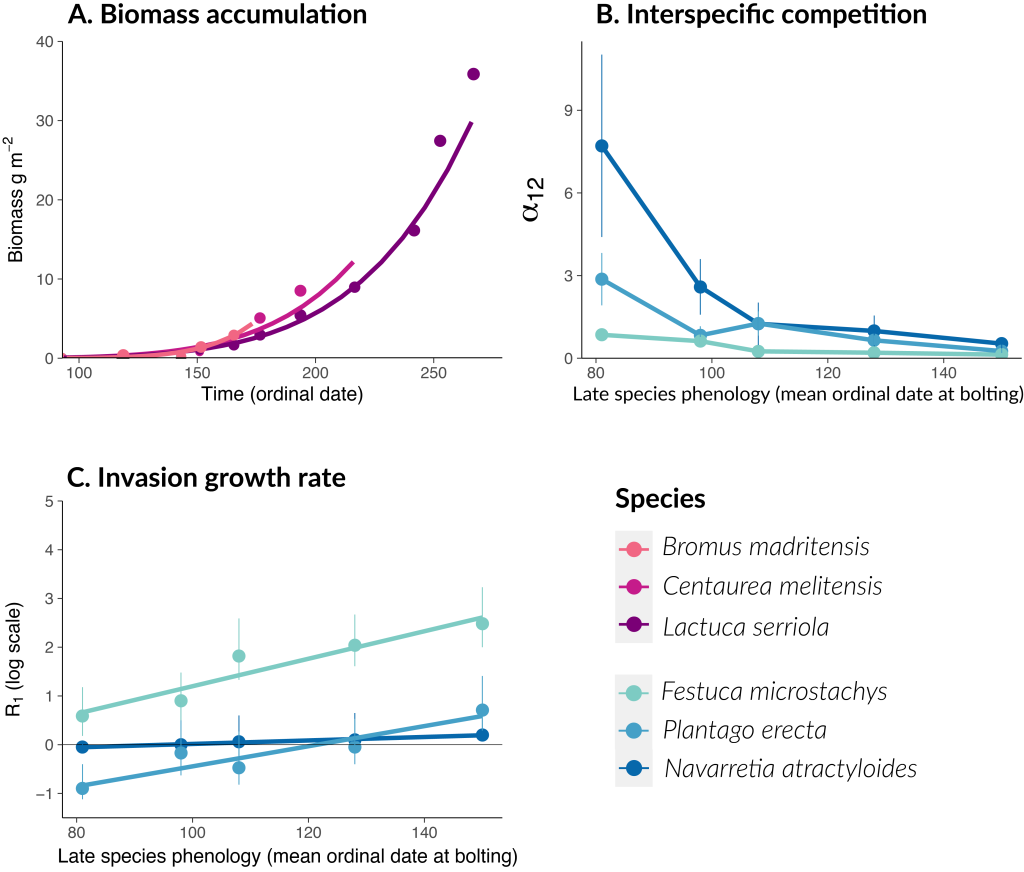

Understanding how diversity is maintained in plant communities requires that we first understand the mechanisms of competition for limiting resources. In ecology, there is an underappreciated but fundamental distinction between systems in which the depletion of limiting resources reduces the growth rates of competitors and systems in which resource depletion reduces the time available for competitors to grow, a mechanism I call ‘competition for time’. Importantly, modern community ecology and our framing of the coexistence problem are built on the assumption that competition reduces the growth rate. However, recent theoretical work suggests competition for time may be the predominant competitive mechanism in a broad array of natural communities, a significant advance given that when species compete for time, diversity-maintaining trade-offs emerge organically.

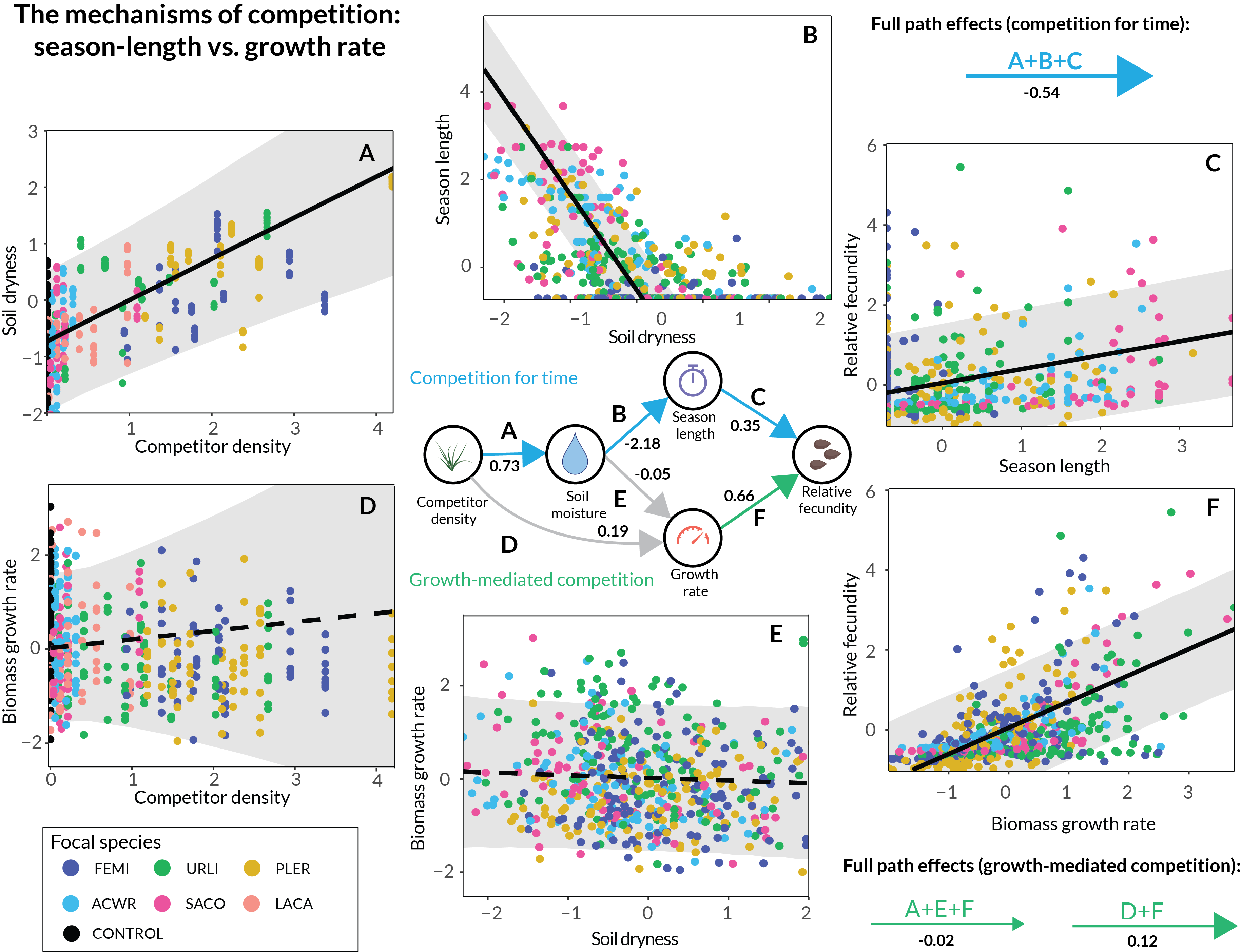

In this study, published this year in Ecology Letters (link), we first introduce competition for time conceptually using a simple model of interacting species. Then, we perform an experiment in a Mediterranean annual grassland to determine whether competition for time is an important competitive mechanism in a field system. Indeed, we find that species respond to increased competition through reductions in their lifespan rather than their rate of growth. In total, our study suggests competition for time may be overlooked as a mechanism of biodiversity maintenance.

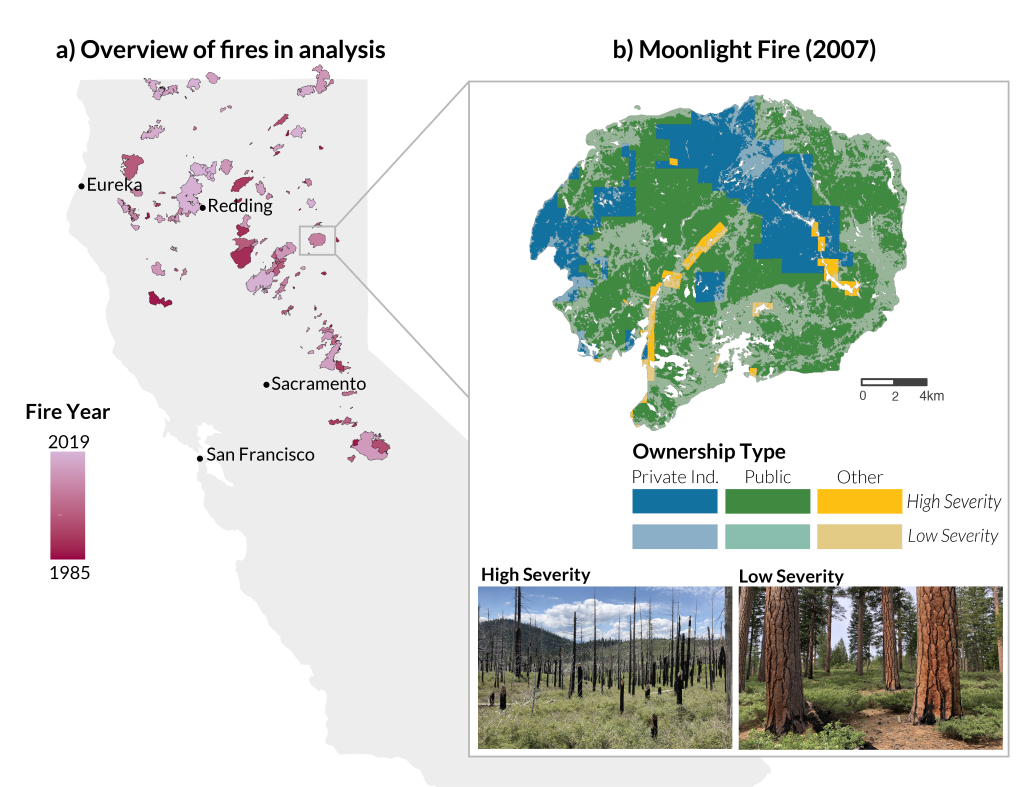

Increased incidence of high-severity fire in industrially managed forests

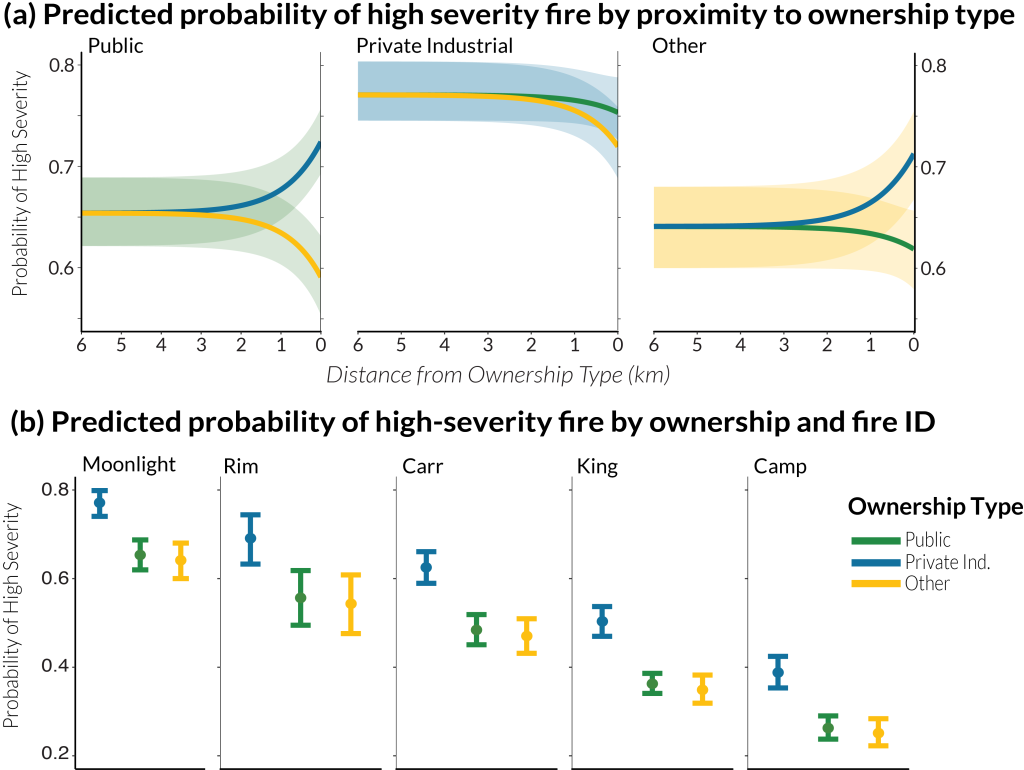

The increased incidence of high-severity wildfires in western US forests over the past several decades threatens both ecological and social systems. This trend is connected to past forest management, but uncertainty remains regarding the differential effects of land ownership on these trends. To determine whether differing forest management regimes, inferred from land ownership, influence high-severity fire incidence, I assembled and analyzed a large dataset of 154 wildfires that burned a combined area of more than 971,000 ha in California.

I found that where fires occurred, the odds of high-severity fire on “private industrial” lands were 1.8 times greater than on “public” lands and 1.9 times greater than on “other” lands (that is, remaining lands classified as neither private industrial nor public). Moreover, high-severity fire incidence was greater in areas adjacent to private industrial land, indicating this trend extends across ownership boundaries. Overall, these results indicate that prevailing forest management practices on private industrial timberland may increase high-severity fire occurrence, underscoring the need for cross-boundary cooperation to protect ecological and social systems. This research was published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment in 2022 (link).

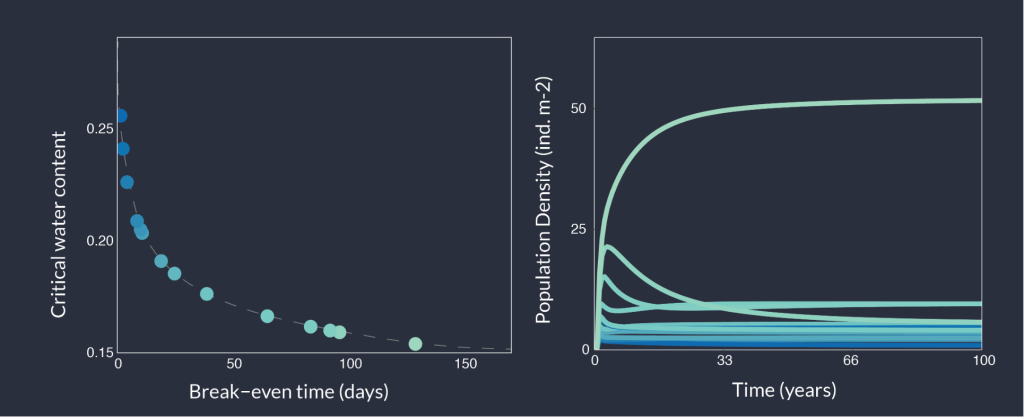

Competition for water and species coexistence in phenologically-structured annual plant communities

Both competition for water and phenological variation are important determinants of plant community structure, but ecologists lack a synthetic theory for how they affect coexistence outcomes. In a 2022 paper in Ecology Letters (link), I described an analytically tractable model of water competition for Mediterranean annual communities and demonstrated that variation in phenology alone can maintain high diversity in spatially homogenous assemblages of water-limited plants.

I modelled a system where all water arrives early in the season and species vary in their ability to grow under drying conditions. As a consequence, species differ in growing season length and compete by shortening the growing season of their competitors. This model replicates and offers mechanistic explanations for patterns observed in empirical studies of how phenology influences coexistence among Mediterranean annuals. Additionally, we found that a decreasing, concave-up trade-off between growth rate and access to water can maintain high diversity under simple but realistic assumptions. High diversity is possible because: (1) later plants escape competition after their earlier season competitors have gone to seed and (2) early-season species are more than compensated for their shortened growing season by a growth rate advantage. Together, these mechanisms provide an explanation for how phenologically variable annual plant species might coexist when competing only for water.